- 28th July 2022

- By Wil Vincent

- 1 Comments

The games are one thing: Legacy is another – A Look at CWG2022 and Perry Barr

The 2022 Commonwealth Games opening ceremony takes place 10 years and a day after the opening ceremony of the 2012 London Olympics, and 8 years 5 days after the opening ceremony for the 2014 Glasgow Commonwealth Games. These three events, and the 2002 Manchester Commonwealth games provides us the opportunity to understand the British approach to designing, implementing, and providing a lasting future for the host city / area, the latter known as legacy. Birmingham has placed most of its focus for development and legacy based regeneration on Perry Barr, located 4 miles north of the City Centre, which acts as a regional hub, and has been developed over time since the late 1800s.

To begin, it must be remembered that this was not Birmingham’s games. It was orphaned to them after Durban in South Africa lost the right to host the games in large part due to spiraling costs and a lack of readiness. The process to award the games to somewhere in the UK was convoluted with issues, with Liverpool’s bid rejected by the UK Government, and Birmingham’s uncontested bid littered with compliance issues. The lateness out of the starting blocks always put Birmingham on the back foot, and this is taken into consideration when considering the output that Birmingham has and will produce, but likewise, why bid for something that you can’t achieve? Birmingham and the Black Country already know this after the years long delay caused by Carillion and the Midland Metropolitan Hospital as an example.

Defining Legacy

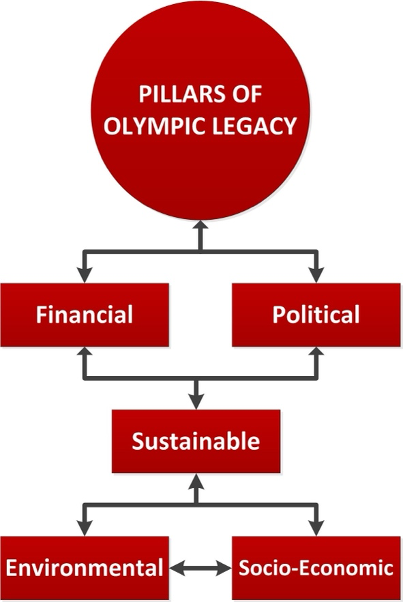

This article focuses on legacy. 10 years ago I watched the opening ceremony of the London games having completed my dissertation on the topic” Olympic Legacy: It’s history, driving factors, and role in shaping renewal projects through London 2012”. Here, I examined previous Olympic game legacy, the determining factors in determining a ‘successful games’ both short, medium and long term, and how this could be used to measure success in the future. My crudish outline was to assess pillars of Olympic Legacy, as shown in the graphic. If I were to redo this, I would certainly change it, but it makes for a good starting point for discussion.

Legacy, or specifically Mega Event Legacy has a variety of definitions, most often one is produced by the candidate / host city of an event to make it look like they are more likely to achieve their ambitions. The IOC have commented on legacy as: “Legacy is our raison d’être. The Olympic Games are more than metres and records. Wherever the games have appeared, cities have changed forever. (Jacques Rogge, IOC Chairman, 2007)”. This is a useful starting point for discussion as whilst Commonwealth Games are substantially smaller than the Olympic Games, the level of local transformation and infrastructure requirements remain roughly scalable.

With the exception of the 1936 games in Germany, most host cities until the 1980s were happy with their ‘legacy’ of hosting the games being seen on the world stage, and from there both an increase in tourism and recognition of the ability to pull off a large scale set of infrastructure and delivery projects. Barcelona ‘re-wrote’ the bidding process and legacy discussion when they chose to use the games to ‘regenerate’ an area of their city, something which has largely been replicated by future host cities (With the exception of Atlanta who preferred to make their city one massive sponsor advertisement). The success of this is limited. Athens, Beijing and Rio have each had issues with crumbling infrastructure, deserted venues and abandoned supporting locations. Only Sydney in 2000 has really been able to make a success of the Barcelona model, and the scale of abandonment and wasted dollars can be an eye-watering prospect to consider.

London, Manchester and Glasgow have all taken this regenerative approach when hosting the Olympic / Commonwealth Games. London chose to regenerate the North East End of Stratford and Newham, Manchester used it to co-ordinate regeneration with new infrastructure and specialized development zones, and Glasgow have used the games to deliver new communities in the City’s East End. At a snapshot level, Manchester as the earliest example has certainly matured and delivered on some of it’s ambitions, and London and Glasgow can argue the same. For the 85% who don’t care beyond the headlines, great.

Snapshot of London 2012 – Legacy Difficulties

Look a little deeper however, and the cracks start to show. London has delivered some new communities in Stratford, alongside one of the largest shopping centres in Europe, with a casino and bunch of restaurants to boot. The Olympic park is nice to walk through, and after being the second biggest white elephant in London after the Millennium Dome, the Olympic stadium now hosts both West Ham United, Major League Baseball, and a bunch of decent music events. I know this as I’ve both been to the MLB and Green Day there, and it’s an impressive setup.

London has only delivered 0.5 & 1% of the houses they promised, and despite there being around 35% affordable houses on these schemes, the word affordable does not mean affordable. Most of the time, this is 80% of market rates, which means that it is still unaffordable for many. The fact that there are some housing association and shared ownership properties helps a little, but one of the bigger issues that residents have faced in these situations is feeling like second class citizens. The gentrification (Or dare I say it, hipsterification) of the area radiating from the Westfield centre has the ‘localness’ that many residents crave in their immediate area; just replace the local fish and chip shop with artisan breads and charcuterie! Whilst there is housing provided and another 6,000 homes on the way, the scale of housing delivery is such that the unlocking opportunities for Newham as a new, sustainable, affordable place to live have not been met. Furthermore the current trajectory of housing delivery continues to move away from initial ideals, which leads a risk to make this devide even further down the line. Even the student accommodation in the Olympic Regeneration Zone costs at least £160 per week, which means most university students won’t be able to afford to live off of their student loan.

An interesting point in Stratford London, which is vital when considering the long term effects of Perry Barr is what happens when you cross the road from Stratford Interchange, to the Stratford Centre and beyond. Whilst there may be a more technical term, I teach and use the phrase severance lines; in short, this is where the money, planning policy or vision stops. The Stratford Centre, compared to Westfield is a place where true Newham residents of generations can complete the shopping necessities required for them and their families. There are shops and market areas to serve specific local communities both inside the centre and along the parade that opens up to ‘Old Stratford’, and along with local supermarkets and other amenities creates a sense of place. It is perhaps interesting how the Stratford Centre acts as a barrier between the old and the new, in some ways shielding each community from each other.

In effect therefore, you have two communities. The first is the community that remained from prior to the Games, arguably more rugged in character, but ‘real’; Many families have lived in the area for generations, and there is a close link between residents, space, community functions and the neighbourhood level economy. The other is a new ‘vibrant’ area, but largely out of reach to many who have called Newham their home, and even for those moving to the area, a mixture of vibrancy and sterility, all in one.

Assessing the journey: Perry Barr.

When I was a student studying my undergraduate degree, I studied at what was called City North Campus of Birmingham City University (BCU). This was a large university campus located on the North Eastern quadrant of Perry Barr. The use of quadrant is important here, as barriers have been a major issue in Perry Barr since the 1950’s and Herbert Manzoni’s grand plan of stuffing flyovers and tunnels through Northern Birmingham. BCU had been a major landowner and employer of the area since the 1950s, with the campus being completed in the 1980s and subsequent services built after being awarded university status in 1992, then as the University of Central England. This included two sets of student accommodation halls, and latterly, a sports centre.

Although not initially, over time, students became a major focus of Perry Barr, hastened after changes to the Higher Education sector in the 1990s then 2000s. This meant that a number of residential areas next to and close by to campus (To the North West) became studentified, a phenonium where students displace residential communities in houses of multiple occupation (HMOs). This is in short driven by the fact that property owners can make 300% more rental income to individual students sharing a house compared to a family, regardless of size. This led to a campaign group called ‘Long Live Perry Barr’ being set up when BCU elected to consolidate it’s main campus to the City Centre of Birmingham, to be… Birmingham CITY University[1][2].

Despite the university’s presence, Perry Barr has long remained a diverse residential and economic community. The area around the main interchange which has caused so much separation for decades is a regional centre, meaning it’s primary purpose is for shopping and other related activities. Walking down this area before work commenced on the games, and you could find pubs for dedicated communities, local shops with goods spilling over onto the surprisingly wide pavement on one side of the A34, and a myriad of local community uses and services. Pretty Perry Barr has never been, however it has always had character, and a well used, yet disjointed setup.

The biggest issue was the massive interchange, junction and flyover which attacked the area both vertically and horizontally. Going from South to North was the A34 flyover, which first tunneled under a roundabout, and then had a small ebb of a final flyover which I never really understood the purpose of. Getting to the One Stop shopping centre required maneuvering through the roundabout by car, and pedestrians making upto three separate crossings either at grade or underground. Horizontally runs the Outer Ring Road, famous for hosting the then (But no longer) longest bus route in Europe, the 11A/C. Add to this a Train Station[3], only accessible from one side of the road, a Bus Station which served Northbound traffic almost exclusively, and yard after yard of metal barrier separating pedestrians from the three-dimensional car / train interchange, and you had a hot mess to get around.

For pedestrians, the options would be to walk around the entire at grade level traffic lights, or use one of the multiple tunnels under roads and roundabouts. One was filled in in 2015(?) in an effort to reduce antisocial behavior, which linked the university to the shopping centre. One had an incident of a body part and a manchette, and the roundabout looked, felt, and smelled unappealing at best. Pedestrian movement was an issue throughout, and on multiple occasions I have placed students at the exit of the train station and asked them to find their way to the opposite side of the road. Whilst locals may know (and be used to) this, it creates massive barriers socially, and for anyone visiting Perry Barr. I think it’s a statement as to the issues of an area that the McDonalds closed after the university campus move happened.

I should add that there is a river also going through Perry Barr, and two large greenspaces on either side of the Northern fringe of the area. The one to the East hosts the Alexandra Stadium, the key sporting arena of the games. This has hosted Diamond League events for years, and both greenspaces are well used by local and semi local communities. It’s not all bad news!

Responding To The Challenges? Enter CG2022

On paper, Perry Barr is the perfect candidate to host the Commonwealth Games. They have a sporting venue suitable and proven in it’s use for Athletics which could benefit from investment, it allows the unlocking of parts of Northern Birmingham (Which is often poorer than the South), and of course, it should allow for the regeneration of a number of sites within the area, most notably that of the former BCU campus. Perry Barr is an area going that can be seen to the gateway of North Birmingham, and strategically follows some areas of regeneration closer to the city core through the Aston Newtown and Lozells. It had previously been identified as potential areas for regeneration through Birmingham Supplementary Planning Documents, though the Birmingham Development Plan’s attribution of the BCU site and it’s surroundings (Policy GA3) amounts to saying that ‘something can be done, make it look and feel pretty’. The policy is so vague that although it identifies the key nodes in the area, it offers zero potential solutions.

In simple terms, much of Perry Barr has suffered a fate in Birmingham where land is vaguely designated, with no joined up vision and a hope that a developer can come up with an idea that will avoid the limited number of Planners working at Birmingham City Council from getting egg on their faces. There are large swathes of Birmingham, particularly in the ‘doughnut’ between the inner and middle ring roads, and along the A34 corridor which largely lacks any long term planning vision, despite the Birmingham Development Plan facing a massive undersupply of housing and associated land to support communities. As a simple example within Perry Barr alone, the former library site alongside the A34 / Outer Ring road has laid neglected both physically and in terms of planning for years, and the lack of real connection between sites outside of strategic areas both stifles development opportunity and the ability to suitably plan for the medium – long term regeneration of areas that need it, without the wholescale change caused my mega development regeneration or otherwise strategic regeneration zones.

The solution put forward by the orgonising committee when putting forward proposals for the 2022 games was simple: Refresh some venues, build a landmark development in Perry Barr, and invest in some transport infrastructure, which included Perry Barr interchange, which included piggybacking off of some existing CIL money. There was to be financed by a multi Hundred Million Budget from Central Government, and the rest to be made up by a bankrupt council which during the preparation for the games ended up having a massive bin strike, and also has historical equal pay issues which led to them selling some of their most prized assets. It was nowhere near as ambitious as Manchester or even Glasgow, but with the time available, it looked to be to do things efficiently and get something done well. Many venues in the Black Country were given some money to host and renovate, possibly as an olive branch over the massive housing supply deficit being provided to them, and on paper at least, the proposals looked reasonable.

I taught a module which required students to look at the former BCU site. One year, I engaged students to look at transforming the site into a student village, based on the lower rental prices and good connectivity to the City Centre; This is something similar to what Derby University do in providing free transport to and from halls, to keep rental prices low(er). The following year, knowing the fact the site had been sold to the Homes and Communities Agency, we got wind that Birmingham had been earmarked to potentially host the Commonwealth Games, so we offered a bold scenario: Build an athlete’s village. Turned out half way through the module, this was identified as the actual proposed use, with retrofitting post games to accommodation to meet the HCA’s needs. Full time students had to do a full design and build submission, whereas Part Time students just had to consider timeframes and numbers. In 2018, they said that it couldn’t be done with the proposals provided… Two years and about 5 months later, that’s exactly what the Organising Committee admitted.

This athlete’s village was supposed to be one of the landmark developments of the games. Something that fans would see as they were travelling on the shiny new Sprint busses up the A34, or whilst doing the 30 minute walk from the new Perry Barr Train Station. The development is now almost complete, though athletes instead are being housed at University of Birmingham and elsewhere. Nowhere near Perry Barr, moving the cameras and attention away from the heartland. This means that development on the former BCU campus is no longer a transformational development, hosting athletes and then new communities to Perry Barr, and are frankly, now just another expensive housing project. The only benefit here is that to my understanding this is still owned by the HCA, meaning that the level of truly affordable housing should still be possible. With project retrofit also cancelled 2 years prior to the games, it’s also assumed that these will reach the market earlier at the very least, offering some form of stimulant to the locale.

Consulting, Pushing Ahead, Causing Division.

The next pillar of regeneration that the orgonising committee pushed through was the leveling off of the roundabout at the centre of Perry Barr, and the removal of the flyover at it’s northernmost tip. Having studied and travelled through the area for over a decade, I never understood that little remanent of Flyover, and have long argued to students and peers that something similar to what was completed would be a benefit to Perry Barr. I have had many student groups offer some useful solutions similar to what was implemented, first removing the scrap and lorry sites in the middle of the entire mess, and secondly simplifying the entire area.

The primary reason for this is that it would remove some of the impenetrable physical barriers around the central core of the region, allowing freer movement of pedestrians, public transport and vehicular travel alike. Never more would I have to be stuck outside Red Onion waiting at the roundabout as another BMW M3 drove down the bus lane to jump the queue, and no longer would pedestrians have to lug pushchairs and shopping trollies up and down stairs and ramps just to cross a road. For car users it would add some journey time on some routes, but the net benefit should be measured for all users…

… This is not how a group of residents took this, and fought tooth and nail to block these proposals, delaying the process at the same time. Our glorious Mayor of the West Midlands Andy Street somehow also supported this protest, either on party line (Just oppose the Labour Council) or populist reasons. Many a social media post had questions as to why he supported this, without a true reason is response. The argument placed was both increased journey times and impact on pollution through the heart of Perry Barr. Whilst I always recognize the importance of protest as a way of drawing attention to issues, I strongly feel that this was solely a bunch of car owners worrying about themselves, having not had to cross from the old BCU campus to get to the Post Office which would require at least 2 at grade / underpass crossings just to get to the right ‘side’ of the area.

Most shockingly however was the level of consultation that was done, and how it was done. There is a statutory requirement to consult on planning applications and certainly development of this scale, but there is little scalability here. So long as you tick the boxes to say it’s been done, you can get away holding a public consultation between 2:30PM and 4:30PM on a Thursday in the middle of a shopping centre. There is also the more important difference that needs to be made between consulting on singular planning applications, and consulting on wider visions. I will not be so brash to say that there was a statutory failure when it came to consultation, though there certainly is a case to be made that the level of this could have been higher, and more specifically engaging to the community. It is a relatively well known fact that metropolitan areas have less engagement with Planning matters compared to rural and I have had personal experience of large sites with less than a handful of public comments. Perry Barr’s diversity could well have proven to be a barrier to true engagement, and this is something which could certainly have been improved of.

This is important as there were a number of Compulsory Purchase Orders that were done as a part of this process, most noticeably around the redesigned train station and the A34 corridor. Remembering that those who own and who rent the buildings are often different, and the consultation and rights afforded to each are again different. Some local businesses who rent ground floor units were of course consulted upon the fact that their business would have to re-locate, but there seems to be a lack of direction in terms of supporting this, especially after the difficulties caused by COVID-19. Like with the 2012 Olympic Games, moving a business even a mile up the road can cause irreparable harm, due to the micro-nature of community and neighbourhood shopping. A hairdresser’s location for example may be intrinsically linked to other surrounding developments such as groceries, specialist products, or the local meeting place for a drink. Moving businesses and residents in opposite directions may break these links entirely, especially as the poorest in our community do not have the ease of using cars to join together the dots.

These are all of course the immediate issues; the stress of displacement, the impacts of roadworks (Which 2 weeks before the games, were still going on), and the general inconvenience of construction projects are issues that have to be factored before the games, but then there’s the conversation as to what happens once the athlete’s have competed in their events, the fans have returned home, and things get back to ‘normal’ (Or as is likely, the roadworks are resumed to finish the job). The medium to long term issues relate to how the developments, infrastructure and communities can seek a long term, sustainable, successful connected future. This is designed to be achieved in a Planning sense by the 2040 Perry Barr Masterplan, which hopes to help connect various visions from the Commonwealth Games and future developments together.

Perry Barr 2040 Masterplan

The fact that it took until February 2022 for the Council’s Cabinet to even ratify the 2040 Perry Barr Masterplan, in an online meeting inaudible to everyone I knew was watching highlights the lack of ground up planning. The document does hold planning weight as a material consideration, however crucially does not become part of the Birmingham Development Plan, or hold the same weight as an SPD. Instead: “Now that the masterplan has been adopted, the council will continue to work with partners and stakeholders to develop a Programme-wide business case and delivery plan. Please check back for more information.”[4]

In terms of consultation to this; aka engaging with the local community of some 23,500 people (2011 Census), a total of 121 responses were received and 600 people engaged with. This translates to 2% of the population with whom contact was made, and 0.5% of the population made responses if we assume only residents participated in this consultation. This of course excluders businesses and those who work but do not live in the area, so the actual percentages go even lower. Going to the actual consultation document provided by the council, 80 direct consultation responses were received, and this showed ‘strong support’ for the masterplan. Whilst it is impossible for the council to actively engage all members of the community, a <0.5% response rate means that it is harder to justify true engagement, especially as two petitions received more signatories than the overall consultation, and social media comments on the flyover as a singular example far outweigh this.

On the topic of social media, there seems to as always be a lack of local, ‘meeting people where they are’ level of engagement. Whilst the consultation document considers a range of methods of advertising the consultation, the reliance is on individuals to go to a platform of the council, rather than the council seeking responses using social and interactive media, for example Nextdoor, Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. As there are a number of ethnically diverse communities within the region, obvious to the Council via census and other data, it’s almost shocking to see the lack of dedicated local level engagement with community groups and communities in the way that they meet, engage and interact. For the first time in this piece, I would argue that whilst this is an English Planning system, the way of engaging with the communities within Perry Barr is inherently exclusionary, using techniques that engage majority white, rural residential communities, and not other ethnically diverse communities at a joined up / separate level.

Because of this, the Perry Barr 2040 Masterplan provides a vision that itself can be argued to be counteractive to the communities that already exist within Perry Barr. This can be easily demonstrated in the fact that the focus areas of the Masterplan show Perry Barr Village, Perry Barr Urban Centre and Walsall Road and River Tame Corridor as three separate areas that do not even represent the true societal boundaries where people live, work and interact highlights the lack of true consultation, engagement and recognition as to what Perry Barr is in 2022. To be truthful and frank, a part of this feels like sometimes the policy makers have not even been to site to truly understand the area; how can you stop the Urban Centre before you even take into account the majority of the Southern shopping area? I know that the building where Red Onion and the Post Office lives deserve to be demolished and redeveloped en haste, but the boundaries alone make no sense at all. Phrases such as “Local retail, cafes, community uses, local services and facilities will all bring a buzz of activity to the area at different times of the day, week or year.” Seem so generic that it could have been bought from an essay bank. There is no way of determining what a LOCAL is in this area due to at least three separate communities merging together!

Because of this, the Perry Barr 2040 Masterplan provides a vision that itself can be argued to be counteractive to the communities that already exist within Perry Barr. This can be easily demonstrated in the fact that the focus areas of the Masterplan show Perry Barr Village, Perry Barr Urban Centre and Walsall Road and River Tame Corridor as three separate areas that do not even represent the true societal boundaries where people live, work and interact highlights the lack of true consultation, engagement and recognition as to what Perry Barr is in 2022. To be truthful and frank, a part of this feels like sometimes the policy makers have not even been to site to truly understand the area; how can you stop the Urban Centre before you even take into account the majority of the Southern shopping area? I know that the building where Red Onion and the Post Office lives deserve to be demolished and redeveloped en haste, but the boundaries alone make no sense at all. Phrases such as “Local retail, cafes, community uses, local services and facilities will all bring a buzz of activity to the area at different times of the day, week or year.” Seem so generic that it could have been bought from an essay bank. There is no way of determining what a LOCAL is in this area due to at least three separate communities merging together!

To be frank, the Perry Barr Masterplan is designed to provide a nice way of demonstrating that there is a future for Perry Barr after the Commonwealth Games, but despite their ‘Highly Commended’ RTPI placemaking award, the imagery and text does not align to the Perry Barr of today. Whilst urban boulevards with cafes spilling out onto the street sounds lovely, and aligns to the Perry Barr village, this does not align to current communities who have already had their community and leisure uses in some cases removed by the same development ideas which now replace this. I called the Masterplan racist in a lecture in March 2022, and to be honest, I don’t think that I need to walk back from this position. At best, it’s racially and community level insensitive, at worst, it serves to perpetuate the same issues which has caused the Stratford developments to isolate itself from the communities that surround it… Maybe just without as much of a buffer.

Where’s The Legacy Though? Short Term

Whilst writing this article, on ITV’s Evening News Ian Reid, who is the Chief Executive of Birmingham 2022 stated that they “Continue to evaluate it 1, 2, and 5 years into the future, as” there is the need to consider the long term future, as “That is the power of these events that they deliver these long term benefits, as if that doesn’t happen, then yes we’ve not delivered on what we should have”. Almost by accident, this may highlight the exact issue that Birmingham are facing when looking towards the long term legacy for the city. Andy Street keeps posting about Birmingham hosting more world class events over the next 8 years, but there is little discussion about the local legacy for actual people in the long term outside of the 2040 Masterplan.

One thing to get out of the way quickly; the Alexander Stadium (Or part of it) will be transferred over to Birmingham City University for their Sports Science courses after the games. Despite BCU not being a sponsor of the games, they are set to benefit on paper at least from the investment had. Memory and 3rd hand knowledge reminds me that this could be a land swap of sorts, so even though the university gets the value of the regeneration, this certainly was not an act of charity or grace, and like the West Ham Olympic Stadium agreement is one that could be looked back on for value / success in years to come. The fact that the venue had and will continue to hold world class athletics competition is a clear plus, and the BCU element will hopefully offset the longer term maintenance and management costs that are often forgotten about post mega event.

To call the former Perry Barr Train station an unwelcoming place would be an understatement. Flanked by an Age Concern charity shop on one side and Uni Pizza 3 doors down on the other, the surroundings were not the most inviting. Worse was the long metal guardrail that ran exactly 1.8M in front of the entrance, to the left, to the right, as far as the eye can see. The train station has been replaced via some compulsory purchases, although the plans proposed and plans delivered varied as much as buying a cheap and cheerful Christmas tree at Latiffs in Birmingham City Centre. Whilst University station at the University of Birmingham have had all of it’s design visions enacted, Perry Barr has had to resign itself to the backup backup option.

Despite the station design being transformed into a rusting box, the bigger issue relates to how a key opportunity is missed in providing platform access on both sides of the A34. Despite Jordan Quinlan, Transport Planner for Birmingham City Council telling TimeOut Magazine ‘Perry Barr’s new housing development is a high-quality, gently densified new community that prioritises public transport and active travel,’ not providing platform access from this new development highlights the systemic level of cost cutting, and lack of long term focus on providing the opportunities for the dots to be joined together. One of the successes of the redevelopment of Stratford Station in London was the ability to allow passengers to connect to both the ‘old’ and the ‘new’ Stratford, including one of the few times the tube doors open on both sides on the Central Line platform.

This at least does provide a catalyst for future interconnectivity, and the opportunity to join up Perry Barr, along with the associated bus station. This can be considered as legacy development, as although CIL Reg123 list money was being used for this project, the Commonwealth Games enabled this to be delivered quicker, though one could argue that this means that more money may need to be found down the line to retrofit some of the points made above. This all ties in alongside the Sprint system, providing bus-like trams, which provides rapid transport from the City Centre (in this case) to the North of the city, prioritising this traffic over other vehicular traffic despite sharing road space. Even though this was implemented in time for the games, it was scheduled to be delivered alongside a larger transport strategy anyway, so this is less impactful in terms of direct legacy gain.

The flyover and changing of pedestrian priority when moving around Perry Barr is further designed to remove the physical and social barriers which have haunted the region for decades. Whilst hated by some as a matter of principle and by more due to the delays of over 3 miles through the area at 20MPH, the true impact and success of this cannot be felt until at least a year after the games, as it’s likely work needs to be finished and time taken for pedestrians, public and private transport to adapt to the new hierarchy of space and navigables around the area.

The last true legacy development of the games is the formerly designated Athlete’s village. This will provide new housing, and as discussed previously mentioned, the fact that the site reverts back to the Homes and Communities Agency provides some hope that this will provide a less volatile situation in terms of affordability compared to Stratford. Birmingham City Council’s literature states that “Up to 99 homes on the site will be available for first-time buyers as part of the First Homes Early Delivery Programme”. (Though up to of course is an ominous, non committal figure).

In short therefore, the direct legacy outcome in terms of physical structure in Perry Barr is limited, but this was always what the games should have done, as it was also designed to help regenerate other venues such as the Sandwell Aquatics centre, so there is a positive physical legacy felt in part throughout the Black Country as well as Birmingham. This as mentioned does help lessen the negative feeling towards Perry Barr being a money sucker, especially at a time when a number of Local Authorities in the region struggling run basic services, let alone fund large scale infrastructure developments.

Longer Term Legacy: The Reality

As mentioned at the start of this piece. Until Barcelona, legacy often was introducing (Or re-introducing) a city or an area to the world stage. In fact Birmingham bid for the 1992 Olympic Games against Barcelona for this exact reason. Alongside Andy Street’s ambition for Birmingham to host more world class events over the next 8 years, this could be seen as a legacy objective to re-introduce Birmingham onto the World stage, and arguably fight Manchester for the title of ‘Second City’. There is a lot at stake here way beyond Perry Barr, considering the way that industry and commerce invest in the Birmingham region, which is something that Manchester has outpaced Birmingham at over the past 20 years, in part due to the joining up of the Commonwealth games with other regenerative efforts such as Salford Quays.

In terms of Perry Barr, the Perry Barr Masterplan looks like it was developed with a metaphorical gun to the head, forcing them to come up with something. Birmingham has often be vague in terms of delivery masterplanning, instead allowing developers to shape their own vision, rather than confirming to a pre-defined set of boxes. That being said, the Masterplan as read really does not consider many of the 23,500+ residents who live there, along with the multitude of local, independent businesses who have survived and flourished over the past few decades. This is not saying that every business in Perry Barr is successful, but outside of the One Stop Centre, there is a distinct localness to the area in terms of business and community functions, much like in ‘Old’ Stratford. The Masterplan almost seems to want to sanitise the area, and whilst arguably wanting to promote independent business, makes no guarantee that this will be uses compatable with existing communities. Even in terms of the One Stop Centre, the vagueness and discussion seems to want to make the centre ‘better’, but better for who?

Birmingham will have to review their Birmingham Development Plan soon, and think about how the elements of the Masterplan can be realized into actual opportunities to meet the city’s chronic housing need, whilst supporting the one element that Prince Charles said in the opening address of the games; the diversity of the City and the people who live within it. Perry Barr is already littered with small sterile developments which fail to interact with the rest of the area, and the Masterplan as shown seems to make the prospect of joined-up, true placemaking involving all sectors of the community worse, not better. If this is to be the founding document for considering the legacy objectives of Perry Barr, then alarm bells should be ringing.

Of course, development and placemaking is only a small part of legacy. There is the social and environmental aspects that need to be considered, the latter of which is covered to a more agreeable level in the Masterplan. Utilising Perry Hall Playing Fields, the River Thame, and the network of potential green links to create walkable spaces through the region is something that can be easily achieved, to better unlock more real East West connections. In fact, this is the most likely legacy ‘win’ of the entire masterplan as it can be built into future CIL charging schedules and other environmental policies within the Birmingham Development Plan, and as mentioned previously, both Perry Hall Playing Fields and Perry Park are well used spaces, largely respected by the communities that use them. Combining a network of formal, semi-formal and informal green links will only help to serve all communities, and there is a need to ensure that all new development links into this at a regional level, rather than just being localised isolated spurs.

On a social level, much of what has been written here applies wholeheartedly, and I don’t think much more needs to be said. The links between Perry Barr, Hamstead to the West, Aston to the East and Great Barr / Kingstanding to the North needs to be considered carefully so you don’t end up pushing the poorer communities in society further and further out, and this requires a level of care in placemaking and development management. Geography wise, this is helped in terms of wards and voting towards political parities (Labour, with a Father and Daughter combination spanning much of the region North of Birmingham), but the key factor remains that this needs to wholeheartedly consider the actual needs of all sectors of community and therefore not just ‘consulting’, but getting into the heart of these communities to both understand how to improve their quality of life, but also limit the negative impacts of policy and development decisions. At the moment, I strongly believe that this is being ignored by Birmingham City Council, possibly in part due to the chronic shortage of Planners and those skilled to lead such community engagement.

The risk medium term socially is simple: New shiny developments price out both the residential and commercial sectors of Perry Barr as is today, fragmenting existing communities alongside providing sterile environments for new communities to the area. This has been the case in London, and to a lesser extent Manchester and Glasgow, and is always the hidden loss of large scale regenerative change. It needs to be remembered as well that Perry Barr has a mixture of rental and ownership markets, and the impact of change impacts both groups in different ways.

Finally in terms of the higher level financial and political drivers of legacy delivery, this is simple: Birmingham City Council is broke, and there seems to be little end in sight here. Therefore any real regenerative change will have to be completed either by public-private partnerships with the Council offering concessions to their vision, or, as is the case through the vagueness of the Masterplan and Birmingham Development Plan, be vague, and let private developers provide their own vision. Ironically, it is here that Conservative Andy Street and a Labour led Council can agree on something. One wants brownfield development, the other wants to see regeneration pushed forward. Done correctly, both win. How the council approach the Birmingham Development Plan review, and move towards firming up this Masterplan though, is anyone’s guess.

TLDR: The Summary

Birmingham chose to host the Commonwealth Games with best intentions. They’ve failed already in delivering one of the key aspects of this on time, let alone on budget, but the games have begun, and the lights didn’t go out like the one time at the Superbowl. The coming weeks will show how Birmingham can present itself on the world stage, and 90% of the memories of the success of the games will come from this.

How Birmingham City Council plan to move forward from the games towards delivering a lasting legacy in Perry Barr however is currently vague at best. Engagement to date has been pitiful for something that will shape the area for the next 20+ years, and there seems to be little real consideration as to how new developments and visions will integrate with the 120+ year old communities in Perry Barr and nearby Aston and Hampstead. Current plans look cut and paste, alien to how existing communities use and navigate the area, and questions remain as to how the landmark development in the area will fit into the fabric of the regional centre.

There is still time to fix this; the long term financial issues at Birmingham City Council, and the potential lack of future funding to help join together separate strands of this Masterplan and vision could well be it’s first undoing. The current vagueness can be used to re-engage, re-connect and re-imagine Perry Barr’s future, but there’s realistically only one more opportunity to do so before time, funding and developmental will runs out. Perry Barr’s vision is for 2040. They have till the end of 2023 to nail it, so as not to lose all the momentum it gained by hosting the games.

[1] Fun fact, before this, Aston University was in the City zone of Birmingham, and BCU was in the Aston ward of Birmingham.

[2] For a short time, the university was even stylized like this, with the word CITY in capitals, in part due to a legal dispute with the University of Birmingham.

[3] The oldest train station in the UK in it’s original location.

[4]https://www.birmingham.gov.uk/info/50253/perry_barr_regeneration/2388/perry_barr_2040_a_vision_for_legacy/4

Wil Vincent

30 Something year old Academic at Birmingham City University, teaching and researching in the fields of Planning, Decision Making and Professional Development.Moonlighting expert as an Esports Project Manager, Commentator and Brand Manager. Over a decade's experience in commentary, working with major automotive brands and Esports Sim Racing companies.

Mark

September 15, 2022 at 2:02 am

Thanks for your blog, nice to read. Do not stop.